A deep dive into performance monitoring within LXCs

My last blog post on sharing a GPU with multiple LXCs was meant to be a comprehensive guide on just that one topic. I’d found quite a few guides that gave me partial answers on how to accomplish this, but there wasn’t a one-stop shop with all of the information. One thing that frustrated me to no end, was the fact that intel_gpu_top from the intel-gpu-tools package, did not work in an unprivileged LXC without modifying the host’s kernel and no one seemed to have dug deep into “why” from what I could tell. I thought I had found a way to get this working safely thanks to the errors I received while writing that guide. However, as I investigated them more thoroughly, I realized answering this question would require a deep knowledge of multiple subdomains outside of virtualization including: AppArmor, and the Linux Kernel itself. A deep knowledge I have to be humble enough to admit, I don’t have.

While I’d love to share a solution, I can’t. Instead, I want to share what I learned from my deep dive, and why pending more information I’ve come to the definitive conclusion that it is 100% not possible to do safely today.

False Hope

After fiddling around with the root user for a bit, I decided to properly set up my container with a normal user like I would do in prod. Once I had done this, I found if I run intel_gpu_top in the LXC as that normal user I get the following error which is a bit more helpful than the one liner I got as root.

| |

Knowing the background on uid and gid mapping, namely that privileged users and groups are mapped to unprivileged IDs between the LXC and the host, you might think like I did that we’re just missing a permission on our LXC’s host-side root account with the UID 100000. All we need to do is add that permission and things should work. However, if you dig into the kernel documentation on perf access control, you’ll see that things aren’t so simple.

Kernel Capabilities

For instance, CAP_PERFMON that is called out by intel_gpu_top as required, is not a user level permission. Rather, it is an executable permission we need to give to /usr/bin/intel_gpu_top. Obviously, if we do this on our host it won’t have any affect on the container. The same is true in the reverse, if our LXC gives it’s copy of /usr/bin/intel_gpu_top the CAP_PERFMON capability that is all well and good as far as the LXC is concerned, but as soon as that process is sent to the host and the ID of the user calling it changes to 100000, per the capabilities man page CAP_PERFMON is stripped off along with any other capabilities of intel_gpu_top’s process and it fails with the exact same error as before.

Effect of user ID changes on capabilities

To preserve the traditional semantics for transitions between 0 and nonzero user IDs, the kernel makes the following changes to a thread’s capability sets on changes to the thread’s real, effective, saved set, and filesystem user IDs (using setuid(2), setresuid(2), or similar):

If one or more of the real, effective, or saved set user IDs was previously 0, and as a result of the UID changes all of these IDs have a nonzero value, then all capabilities are cleared from the permitted, effective, and ambient capability sets. If the effective user ID is changed from 0 to nonzero, then all capabilities are cleared from the effective set.

In another section of the perf events and tool security documentation for the Linux Kernel we learn that it’s possible to create a privileged group for performance monitoring. So lets just create one of those groups, pass it through to our LXC, and add our root user on the LXC to that group. In theory, we should be able to use intel_gpu_top without issue after performing these steps. Except that’s where things get even weirder. I performed these steps as a test, following the same rules for mapping the GIDs as previously.

On my proxmox host and the LXC, I created a user with the UID and GID of 5000. For simplicity, I just called them perfmon.

| |

I then changed the ownership of /usr/bin/intel_gpu_top on my proxmox host to make the perfmon group the owner, and set the permissions to restrict the file according to what is on the kernel.org documentation.

| |

I then changed some lines in /etc/pve/lxc/100.conf to allow this user to be passed through to the LXC. Just for testing purposes, I also decided to pass through the whole /usr/bin/ directory on the proxmox host to the perfmon’s home folder inside the LXC, just in case there was something with this capability needing to be set by the proxmox host’s root user specifically (not recommend for what are hopefully obvious reasons). So now all of the lines I’ve added to my LXC config now look like below.

| |

Lastly, let’s get ridiculous on the proxmox host with the kernel capabilities of intel_gpu_top. The below command goes way above what should be needed for this binary (remember to clear these afterwards if you’re following along).

| |

And let’s not forget the /etc/subgid and /etc/subuid changes we need to make. Adding the following to each file.

| |

Ok. First, lets test to make sure I’ve set the user up correctly on the proxmox host. Here goes something!

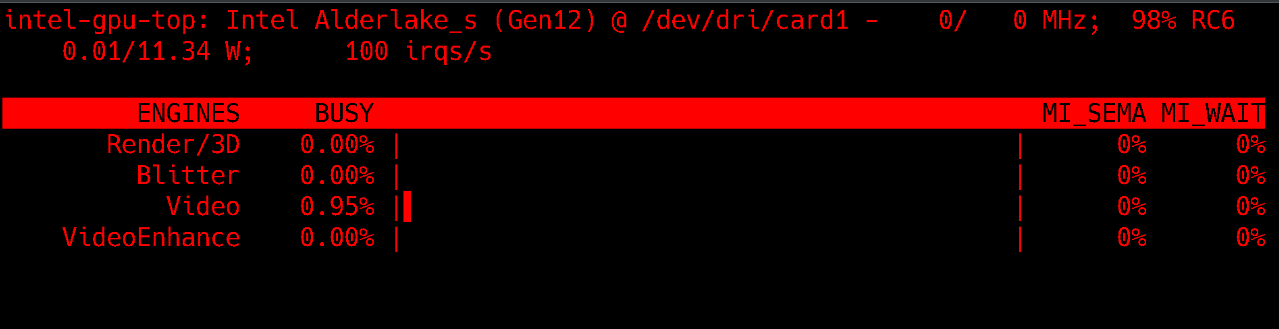

| |

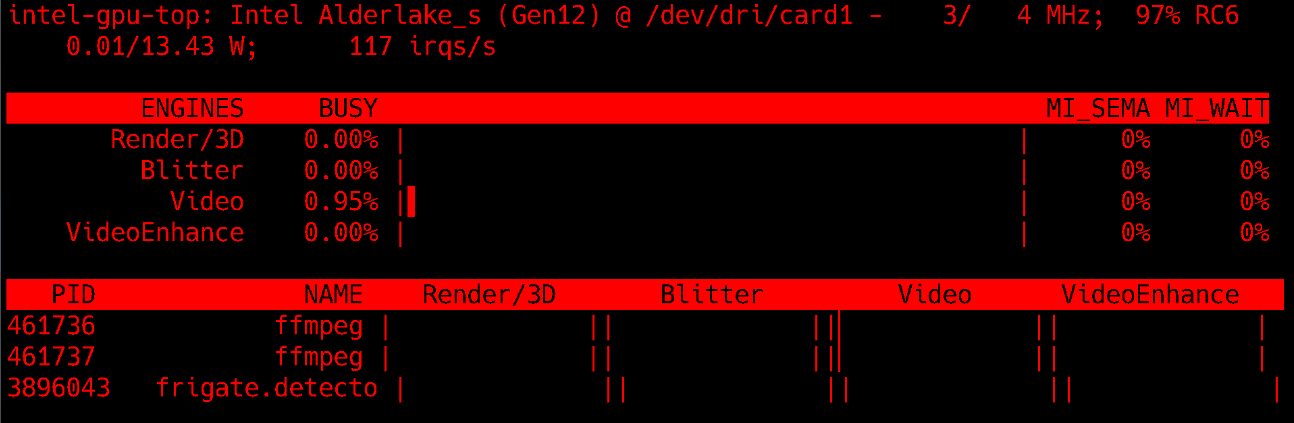

Looks good for the most part. The only problem is, I don’t see any processes like I do for the root user, but this is likely because perfmon isn’t running any processes itself. I know in privileged LXCs even though intel_gpu_top works it only shows the PIDs of processes owned by that LXC. Maybe I can create this perfmon group to map to the root user in the LXC. That’s a problem for the future right now though. Here’s how it looks on the root user for comparison.

After all this, surely intel_gpu_top will now work in the unprivileged LXC. Let’s give it a shot!

| |

Additional Layers of Security

At this point, some curse words may have been uttered. However, in retrospect this makes sense. Remember, UID and GID mapping is not the only way the host is protected from unprivileged LXCs. Linux containers also take advantage of AppArmor to lock down the LXC to only those resources they’ve been given access to. Again, for testing purposes we can disable AppArmor fairly easily by adding the below to the config.

| |

But even when this is done, the permission denied error persists. The only way I have gotten this error to resolve, is by changing perf_event_paranoid on the host’s kernel, or by setting the LXC to privileged which gets around the UID remapping problem we keep bumping into, but we lose that protection as well.

I’m not completely sure why this continues to fail, but at this point I have a hypothesis. A privileged LXC is started with certain capabilities such as CAP_SYS_ADMIN. This is why in our LXC.conf file we could add entries like lxc.cap.keep: perfmon or lxc.cap.drop: sys_admin. However, I don’t believe that unprivileged containers start with these kernel capabilities. So telling our LXC to keep perfmon if it never even had it, will have no effect. And since the process spinning up intel_gpu_top does not have the cap_perfmon capability, it cannot spin up a process that requires it.

The capability bounding set acts as a limiting superset for the capabilities that a thread can add to its inheritable set using capset(2). This means that if a capability is not in the bounding set, then a thread can’t add this capability to its inheritable set, even if it was in its permitted capabilities

Libcap

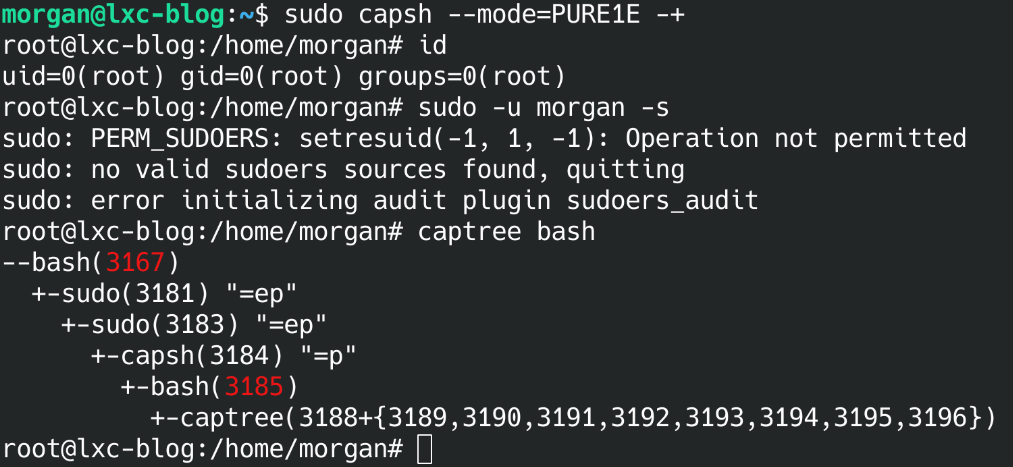

I was definitely missing something and wanted a way to test my hypothesis. So I went back looking for any more discussion on the Linux’s Kernel’s Capabilities and I stumbled upon the official site for libcap. I really do encourage you to take a look at it. That site contains a treasure trove of information about Kernel capabilities and how permission works on Linux in general. The authors have gone to great pains to make it approachable and provide tutorials with fun party tricks like ripping away a root bash process’s privilege, so you get permission denied errors when you try to switch to an unprivileged user.

What I learned from this foray into libcap, is that Linux operates in a hybrid mode of privilege. Some privilege is handled by executable capabilities like I had found in the kernel documentation, some is handled by users like I’ve been familiar with in the past (they call this the legacy privilege model), and lastly you can inherit executable permissions down a process tree. The best piece of information I was able to find there was how to compile and use captree which shows the current capabilities of a running process. When I did that and lowered my perf_event_paranoid back down to 0, I discovered that the process running intel_gpu_top (and it’s parent bash process) in my LXC had all capabilities inside and outside of the LXC. I was barking up the wrong tree, and my hypothesis was wrong.

| |

Seccomp

At this point my trail is starting to run cold. I’ve disabled AppArmor, and the processes I’ve been fighting this whole time seem to have the capabilities to do the job I want them to do. The problem has to be somewhere else. I checked the proxmox documentation once again and in the technology overview I seem to have ticked most of the boxes on access control, but there’s a few I haven’t touched like cgroups and seccomp Well, I’ve gotten this deep so far, what’s the harm in going a little further?

The control group documentation seemed a little out of my depth at the moment so I decided to come back to it. I found an old stack exchange question pointing out how disabling seccomp could enable root to escape the LXC. Bingo, this might be what I want. Well, I certainly don’t want root to escape the LXC, but maybe I can massage the settings of seccomp to get intel_gpu_top out of whatever funk it’s in. Looking around on my file system I meandered over to the LXC’s actual files (not just the conf file that gets read by proxmox) and I found the default seccomp rules for my LXC at /var/lib/lxc/100/rules.seccomp.

Opening them up I see this information. I don’t know what much of it does right now, but the debian lxc.conf man page seems to indicate the 2 is the version number for seccomp and then there is a deny list below this for which I can set optional errors to appear in the seccomp logs when these system calls are encountered. I can add an allowlist in here if I’d like, but for now, let’s disable the entire thing just for testing purposes.

This is what I started with.

| |

And here’s what I ended up with.

| |

Hopefully that means I’ll not be denied anything, again, just for testing purposes. I’m going to copy these new rules over to /etc/pve/lxc/unconfined.seccomp and then in my 100.conf file back at /etc/pve/lxc/ I’ll add the following to the bottom so these rules are enable instead of the defaults.

| |

After restarting the LXC, I then tried to run intel_gpu_top from within it once more, and once more I encountered the error we’re so familiar with.

| |

Control groups

I’m more hopeful about cgroups after reading the intro to them on the redhat blog, but I’m going to temper my expectations. My understanding of their purpose is to facilitate resource sharing on a Linux device by limiting the amount of CPU, RAM, etc that a process is allowed to consume. It seems to me, some of the segmentation of an LXC is accomplished through these means so I’ve got some more reading to do.

A brief glance looking at /var/lib/lxc/100/config shows me quite a few cgroup options in addition to the ones I’ve added for the GPU device passthrough, but nothing immediately jumps out at me as responsible for intel_gpu_top’s failure so I won’t hack and slash it like I did to secomp and AppArmor (yet).

| |

Out of curiosity I created a privileged LXC to see if it’s config looked any different. As far as cgroup settings go, unfortunately the answer is, not really.

| |

An Incomplete Conclusion

This whole cgroup business is starting to seem like a rabbit hole that may take a whole other blog post to run down, so for now I’m going to stop here. Hopefully this post can serve as a starting point for someone else trying to get to the bottom of this (admittedly pointless) issue. Or, perhaps it will serve as an explanation and cautionary tale for the overly curious such as myself who simply won’t take “it doesn’t work” for an answer (and maybe they should just take that for an answer sometimes).

While I didn’t end up achieving my goal, I now understand the fundamental technologies behind LXCs far more than I did before starting this project. Prior to looking into this, I had no idea kernel capabilities even existed despite enabling one of them in my frigate docker-compose (again, don’t blindly copy configs). Now that I know about these tools, I’ve gone back and reviewed my docker-compose and other container configs to remove unnecessary capabilities and so far everything is still working swimmingly.

I also only had a surface level understanding that it was generally safe to over-provision certain aspects of your hypervisor when using LXCs, but I didn’t know why. Now, I do. Cgroups limit the amount of resources a process can utilize, but they don’t just assign a CPU core or patch of memory to a container directly. Rather, they simply limit the amount in use at any given time. So if I have a 4 core CPU on my host and I assign two LXCs 3 cores each, so long as they never exceed the 4 core total between themselves the system will be stable. And most importantly, when an LXC is only using 1 core, the two extras I’ve assigned to that LXC are still available for other processes on the host.

Still, the fact that there seems to be a bit more black magic going on within an LXC will bug me in the back of my head. Particularly why the perfmon group attempt near the beginning of this post failed if they’re mapped to the same user account. While a solution to this issue may lie somewhere in the differences between a privileged and an unprivileged LXC, one thing that’s sure is I won’t be finding it today. This journey has given me an immense amount of respect for all the people behind Linux Containers and the Kernel. There are a lot of moving parts that make these systems function securely, and after digging deep into them today it’s clear that after 5 years as a sysadmin I’ve still only barely scratched the surface of understanding. There is so much more to learn. Isn’t that exciting?